The Legacy of Segregation and the Journey Toward Integration in Carroll County

Early Segregation in Carroll County: 19th Century to Early 20th Century

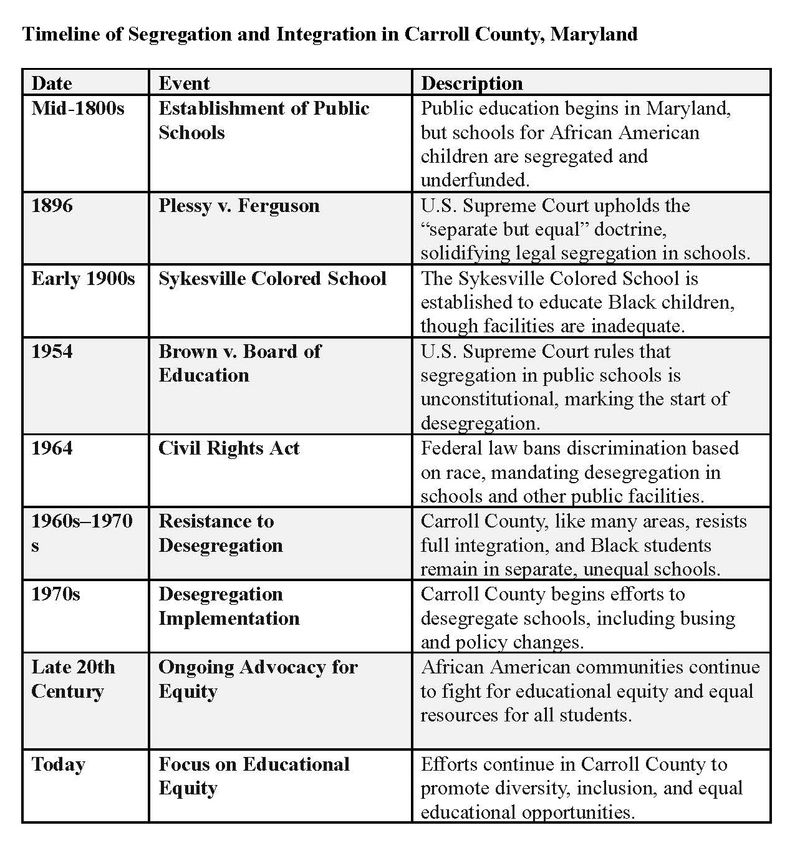

Public education in Carroll County, like much of Maryland and the South, was racially segregated from its inception. In the mid-1800s, public schools were established in Maryland, but African American children were segregated into schools that were underfunded, overcrowded, and offered inferior resources compared to white schools (Maryland State Archives, 2015). Despite the end of slavery in 1865, African Americans in Carroll County struggled to access equitable educational opportunities. The formalization of “separate but equal” laws following the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 further entrenched racial segregation in public schools (U.S. Supreme Court, 1896). This doctrine allowed segregation to continue under the guise of equality, although, in reality, Black schools in Carroll County were woefully inadequate in terms of facilities, funding, and educational resources (Carroll County Times, 2016).

By the early 20th century, African American schools like the Sykesville Colored Schoolhouse became symbols of the disparity in educational access. These schools were 2

overcrowded and lacked the necessary infrastructure to provide quality education to their students (Town of Sykesville, n.d.).

The Rise of “Separate but Equal” and Continued Resistance

The Plessy decision legalized racial segregation, including in public schools, and created an educational divide in places like Carroll County. Throughout the early 20th century, African American children continued to attend separate schools that were distinctly inferior to those attended by white students. African American communities, particularly in rural areas, faced challenges in gaining educational resources and securing trained educators. The struggle for educational equality was compounded by the broader racial discrimination that permeated many aspects of life in Carroll County.

Despite these obstacles, African American communities in Carroll County were not silent. Local leaders and activists, including those connected to the Sykesville Colored Schoolhouse, advocated for better education for African American children, though change came slowly.

The Fight for Integration: 1950s–1960s

The mid-20th century was marked by a shift in the national dialogue surrounding segregation, largely due to the Civil Rights Movement. The landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education overturned the Plessy doctrine, declaring that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” (U.S. Supreme Court, 1954). This decision catalyzed the movement for desegregation across the country, but Carroll County, like many rural areas, was slow to integrate. 3

Despite the Brown decision, local resistance remained strong. Carroll County’s public schools continued to operate under segregated conditions well into the 1960s, with African American children still attending separate, underfunded schools (Carroll County Times, 2016). It was not until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that federal law began to apply greater pressure on local governments to desegregate schools (U.S. Department of Justice, 1964). Yet, even with this legal framework, integration in Carroll County schools progressed at a sluggish pace, marked by local protests, debates, and the political and social realities of rural life.

Slow Steps Toward Desegregation: 1970s

By the 1970s, the momentum for school desegregation reached a critical point. The implementation of busing policies, designed to achieve racial balance in schools, became a contentious issue. In Carroll County, the first meaningful steps toward integration began to take shape in the early 1970s, as federal mandates forced local authorities to dismantle segregated schooling systems (Maryland Historical Society, 2022). While some schools in urban areas had been integrated earlier, rural counties like Carroll lagged behind.

The integration process in Carroll County was fraught with challenges, including public opposition to busing and concerns about the disruption of communities. However, by the mid-1970s, most public schools in the county were officially integrated, although disparities in funding, staffing, and educational outcomes between white and African American students continued to persist.

The Legacy of Segregation and Its Impact Today

While Carroll County formally integrated its schools by the 1970s, the legacy of segregation continued to shape the educational landscape. African American students, particularly in rural areas, still faced systemic disadvantages that could not be overcome by the 4

simple desegregation of schools. These included inadequate educational resources, racial disparities in achievement, and a continued lack of cultural and institutional support (Carroll County Times, 2016).

The Sykesville Colored School, now a historic site, serves as a reminder of this legacy. It was designated a historic landmark in part to honor the African American students who attended it and the broader struggle for educational equality (Town of Sykesville, n.d.). Additionally, African American leaders like Warren Dorsey have worked to keep the history of Black education alive in Carroll County, advocating for greater recognition of the role African Americans played in shaping the area’s cultural and educational development (Baltimore Sun, 2021).

Continuing the Fight for Educational Equality

Carroll County’s history of segregated schools and the slow process of desegregation highlights the deep challenges faced by African American communities in their pursuit of educational equality. While significant progress has been made since the 1970s, the county’s journey toward true educational equity is ongoing. African American leaders and activists continue to advocate for greater access to resources, equity in educational outcomes, and a recognition of the role of race in shaping educational opportunities.

The legacy of segregated schools, such as the Sykesville Colored School, continues to serve as a powerful reminder of the past and a catalyst for continued efforts to ensure that all students—regardless of race or background—have access to a fair and inclusive education. The future of Carroll County’s education system depends on its ability to address past inequities while building an educational environment that truly serves the needs of all students.

References

Baltimore Sun. (2021, July 19). At 100, Warren Dorsey reminisces about growing up African American in Sykesville, is honored by parks naming after mother. https://www.baltimoresun.com/2021/07/19/at-100-warren-dorsey-reminisces-about-growing-up-african-american-in-sykesville-is-honored-by-parks-naming-after-mother/

Carroll County Times. (2016). The history of segregated schools in Carroll County. https://digitaledition.carrollcountytimes.com/tribune/article_popover.aspx?guid=00e2b16b-470e-4800-86c8-22dfd49cff2e

Maryland Historical Society. (2022). African American history in Maryland. Retrieved from https://www.mdhs.org/

Maryland State Archives. (2015). African American education in Maryland. Retrieved from https://msa.maryland.gov/

Sykesville Town. (n.d.). Historic Colored Schoolhouse - Then and Now. https://www.townofsykesville.org/2155/Historic-Colored-Schoolhouse-Then-Now

Sykesville Town. (n.d.). Sykesville Colored Schoolhouse. https://www.townofsykesville.org/2155/Historic-Colored-Schoolhouse-Then-Now

U.S. Department of Justice. (1964). Civil Rights Act of 1964. https://www.justice.gov/crt/civil-rights-act-1964

U.S. Supreme Court. (1896). Plessy v. Ferguson. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1850-1900/163us537

U.S. Supreme Court. (1954). Brown v. Board of Education. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1952/347us483

5.0 (11 Reviews)

Downtown Sykesville Connection

7566 Main Street, Suite 302

Sykesville, MD 21784

(410) 216-4543

www.downtownsykesville.com